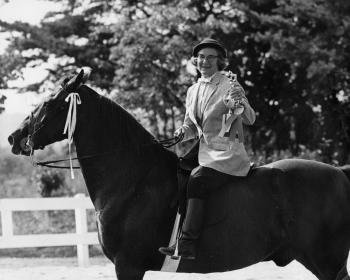

Bettie Watson and Sport, 1976.

In Chatham, the small Virginia town where I was raised, Sunday was the highlight of the week. That was Miss Bettie's only day off.

During many a long-awaited Methodist benediction, I would peek to see Miss Bettie—the only other soul in the place with eyes wide open—leaning perilously out of the choir loft, pantomiming animatedly and holding up two fingers.

And come 2 o'clock, when dishes had been dried and dresses traded for dungarees, I'd head for Miss Bettie's tack house, my pockets bulging with carrots. There, after a ritual of currying hides, evaluating the morning sermon, and picking hooves, we teenagers who were singled out by her favor would board her gleaming gaited pleasure horses.

Ordinary high school kids no longer, we beamed as passersby looked up. And for sunny hours that sped by all too fast, we followed Miss Bettie and her grandiose gelding Sport along forest paths, across creeks, up steep banks, over railroad tracks and down dirt roads. We galloped over pastures and grassy airplane landing strips and paraded proudly through streets of the town.

Bettie Watson and Sport with a trophy, 1974.

Sunday lessons

Initially attracted to her stables by the prospects of riding and show competition, we soon found the main attraction of the place to be Bettie Whitehead Watson herself.

At 65-and-holding, she had an exuberance powerful as the drive of an Indy 500 pit crew and steady as the perseverance of Aesop's fabled tortoise.

Sunday after Sunday, she pointed out deer tracks and blooming rhododendrons along the trail, then returned to put up her horse and work in the yard until long after we shuffled home, exhausted. The manicured shrubbery, continuous blossoms, rows upon rows of fresh vegetables, and the cherry trees of her yard bore testimony year-round to her innovative touch.

On impulse, Miss Bettie would treat us to dinner and a movie or to the Ice Capades in Roanoke. After these occasions, and after every trail ride and show we enjoyed because of her generosity, she thanked us.

1974 Chatham Horse Show officers: Perry Mitchell, Bettie Watson, Paul Shelton, and Lincoln Shelton.

She was always active in church and civic activities, including, of course, the year-long marathon of organizing the local horse show. And when rain ruled out riding, she created the samplers that cover her kitchen walls. “Don't worry so much about your station in life,” one advises. “There is always someone to tell you where to get off.”

Amid all these activities and running her coal and wood business full time, Miss Bettie would tell you that “the most pleasurable part of my life revolves around horses, with a few people mixed in … and I'd rather ride with young people because they'll push you. They're more active and interested. They'll go to any extreme to get the tack clean and get to a show.”

Bettie Watson with B. J., ca. 1975.

B. J.'s antics

Through the years, some 20 horses have munched in the spinach-green pasture running from behind Miss Bettie's yard across the creek to the railroad tracks. She was hard put to name a favorite, although B. J., her big white ambling horse, was often mentioned.

B. J. frequently suffered from allergies or foundering, occasionally bucked instead of cantering in the show ring, shied suddenly on trails, and stepped on people's feet. Just as frequently, he won blue ribbons.

"Horses are just like children," Miss Bettie would say when B. J.'s antics marred yet another occasion. “You never know what they're going to do next. B. J. would get sick and be so ungrateful, yet willing for you to do anything to make him feel better. Then he'd be ready to kick you.”

I could never quite take her all in. If she wasn't firing my ambitions with the sheer contagion of her energy or impressing upon me the limitations of my youth compared to her accumulation of common sense, she was just being entertaining.

Her craziness often manifested itself on special occasions. Once we were at a June show in our jersey jodhpurs, wool socks, boots, coats and ties, and I noticed sweat dripping off the tip of Miss Bettie's nose. I offered her one of the cool white facecloths my mother had packed in Ziploc Bags in the cooler, and she said, “Oh thanks, I needed that,” and proceeded to wipe the horse's face with it.

Aside from wondering how to explain to my mother why even bleach might not salvage the cloth, I tried to figure whether it was that Miss Bettie enjoyed being facetious or that, when she was around horses, she just couldn't focus on anything else.

Bettie Whitehead (Watson), outfitted for July 4, ca. 1923.

First horse

She claims that both her constancy and her fixation on horses evolved from experiences from the first horse she ever rode, back when she was 6 and the “world's worst” tomboy.

“His name was R. D., for our uncle who gave him to Brother. Brother rode that horse to school at Hargrave Military Academy, and I rode behind him to a one-room schoolhouse. He was a horse that could canter from home all the way to town, and I just fell in love with it.

“I kept riding the horse. I rode him three or four years bareback before I ever thought about putting a saddle on him.

“He was just like people, just as temperamental as he could be. I could rake hay with him just fine until he'd take a notion to run away and wrap the rake around a tree.”

"Be what you are"

Youthful Miss Bettie Whitehead (Watson).

Miss Bettie's early days on the farm gave way to marriage, four sons, widowhood and the raising of a niece. Although that outline of her life presents Miss Bettie as the epitome of the ordinary, she was about as commonplace as an Appaloosa at a tea party.

For one thing, she was no ordinary mother. The five-gaited mare that was a wedding gift from her husband helped baby-sit. “She'd ride all the kids and me, in a row like ducks,” Miss Bettie recalled.

For another, she by no means waxed complacent in her well-kept, varied environment. While her sons were in service, she visited them in England, France, Germany, Holland, Spain and most of the Western and Midwestern states.

Miss Bettie's husband F. B. Watson, III (1907-1948).

Yet she never was tempted to move away from her small, middle-American town.

She would bridle at the question of whether her health ever failed as a result of her gallivanting: “You mean besides a cold? I was sick 38 years ago.”

That was for appendicitis.

To stay fit, she said, “I just eat like a horse, sort of, and keep going hard all day.”

Protégés Ann Yeatts (Lancaster) on Sedgemore, and Sarah Atkinson (Armistead) on B. J., with Bettie Watson on Sport, in the Watson pasture.

There were a few other things that helped her keep her pace

“You have to be hardheaded. If you weren't, you'd just get run over.“

And she used to tell us, whenever she saw someone being pretentious or lazy: "Be what you are. It's no use trying to put on airs and pretend you're something you're not. And if you've got something to do, get up and do it. Don't procrastinate."

Many's the time nowadays, when I feel overwhelmed by bank statements, bills and jobs, that I recall those sunny Sundays for which Miss Bettie thanked us.

And I thank her.

Editor's note: Chatham native Laura J. Toler, now of the News Services at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, wrote this story when she was in journalism school.

Bettie Whitehead Watson died Monday, November 27 [1995], at the age of 87. She owned and operated her own business, Chatham Coal, Wood & Oil Co., for 40 years. A horsewoman who won many trophies and ribbons in Southside horse shows, she rode well after her 80th birthday. She was buried Thursday in Chatham.

Photographs are provided by F. B. Watson, IV.

This webpage is sponsored by Mitchells Publications and the Sims-Mitchell House B&B, Chatham, Virginia.

Copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002 Patricia B. Mitchell.