By Henry Christner, Times-Dispatch Staff Writer

Published February 13, 1994

Copyright © Richmond Times-Dispatch, Richmond, Virginia; Used with Permission

Bill Hathaway, an amateur naturalist for most of his 70 years, has an instinct for discovery.

He once found a rare wildflower while smoking a cigar on a rocky bluff above the Banister River in eastern Pittsylvania County. A few years later, on the same bluff, Hathaway stumbled across the fossil of a tiny footprint. It proved to be the track of Thecodont, a Triassic-era reptile.

Hathaway, who has taught chemistry, biology and geology, can think of only one explanation for his ability: “Seek and you will find.”

The same could be said for the Banister.

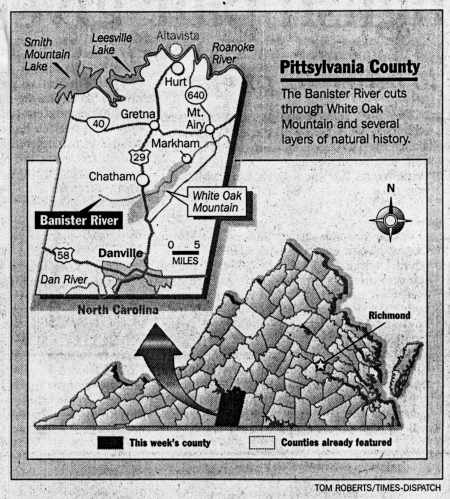

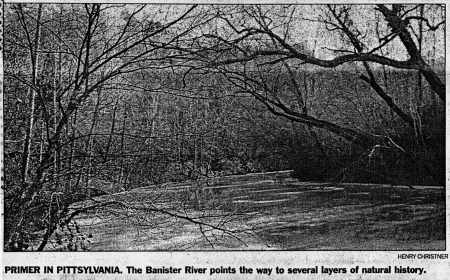

Other rivers in Virginia's largest county are better known, such the Dan and the Staunton/Roanoke, and some have more memorable names, such as the Stinking River and its tributary, Maggotty Creek. But the Banister, which begins as an anonymous trickle in the mountains west of Chatham, is distinctive in its own right because it points the way to several layers of natural history.

As often happens in an ecosystem, every discovery associated with the Banister is connected to something larger.

Hathaway's wildflower proved to be an Anemone berlanderii, a Texas-Alabama native that thrived on the Banister bluff because of how the terrain there is positioned relative to sunlight. A few miles away, this snapshot of survival is echoed on a remote slope of White Oak Mountain.

There, the Banister passes a stand of hemlock trees that give a taste of what this part of the country looked like during the ice age. Says the Audubon Society's Field Guide to Natural Places for the Mid-Atlantic:

These hemlock slopes (along the Banister) are relics of a large evergreen forest that covered much of the Piedmont when the southern United States lay in the shadow of the ice sheet that stopped hundreds of miles to the north during the last glacial advance.

Hathaway's reptile fossil also was part of a larger picture.

The dime-sized track was identified in 1979 by Dr. Paul Olsen of Columbia University, who for the past two decades has found Pittsylvania to be rich with fossils of late-Triassic animals and plants.

The focus of work by Olsen and others since the 1970s has been the basin of an immense lake that once covered the region. Among their discoveries in a Virginia Solite Corp. quarry near the community of Cascade are the fossil remains of a previously unknown aquatic reptile (Tanytrachelos) and the only known deposit of Triassic insects in North America, including the earliest true flies. They also found the fossil remains of ancient conifer forests and the earliest-known flowering plants.

The Banister, which was formed long after the ancient lake disappeared, also points the way to more recent history.

Near the communities of Markham and Riceville, the river contains two fish weirs built by local Indian tribes 300 to 400 years ago. The V-shaped stone structures were used to divert the current and make it easier to catch migrating shad, sturgeon and other species. Later, the weirs were used by colonial settlers and even 20th century fishermen.

The Markham weir is still visible from state Route 683, just below the rocky bluffs where Hathaway discovered his wildflower and fossil. Indian artifacts also have been found there, including bone hooks and sections of harpoons.

The Riceville fish weir is more difficult to find. It lies near the site of an old Indian canoe landing and the ruins of the Fitzgerald grist mill and dam that were built in the 1830s. Unlike other waterways in the county, the Banister had only a few dams and mills in the 19th century because it was used as a major transportation route for tobacco and other products.

The discovery of the Fitzgerald mill site is featured in an educational video produced by local history buff Henry Mitchell, who runs the county school system's planetarium and operates the Sims-Mitchell bed-and-breakfast in Chatham with his wife, Patricia, a cookbook author.

In the video, History and Mystery on the Banister River, Mitchell, Hathaway and others explore the riverbank, and local historian Herman Melton speculates about the Banister's role in the competing worlds of fishing, navigation, and milling.

Visitors who want to learn more about the Banister have several choices.

One is to explore by car. Pittsylvania's historical society has a published pamphlet that shows the way to the Markham fish weir and other sites, such as a nearby stone chimney that marks the riverside birthplace of Rachel Donelson, wife of Andrew Jackson.

Another option is to use a canoe. Sections of the Banister are navigable when water levels are high enough, says Brian Buchanan of the Danville parks and recreation department. He advises checking road maps and scouting the territory first; most of the river is easy paddling, with rapids no greater than Class 1 or 2. Possible put-in spots include the fish weir site at Markham and the bridge on state Route 640 south of Mt. Airy.

For hikers, the best access is the Hiawatha Trail, which begins at a parking area along state Route 649 in the state-owned White Oak Mountain wildlife area [see also Pictures from the White Oak Mountain Wildlife Management Area]. The short trail leads to the riverbank, where the water is shallow enough for swimming, then climbs to a bluff overlooking the remote terrain.

A side loop trail leading to the stand of hemlocks cited in the Audubon guide has been washed away in floodwaters, so finding the trees requires some trial-and-error exploration.

Hathaway, who had a hand in developing that trail, said some of the bigger hemlocks have been destroyed recently by ice and wind. However, many newer trees are doing fine, and Hathaway says he would like to find a way to reopen the old hemlock loop trail.

Given his track record along the Banister, it shouldn't take long.

This website is sponsored by Mitchells Publications and the Sims-Mitchell House, Chatham, Virginia.

Copyright © 1994 Richmond Times-Dispatch (used with permission).